Ogden High alum shares his experiences inside Utah’s Topaz War Relocation Center

- This Shimomura family photo was taken inside the Topaz War Relocation Center in 1944. From left to right: Taka Shimomura, Saburo Sam Shimomura, Kenichi Shimomura, Toshinaga Shimomura, Yukio Shimomura and Natsu Shimomura.

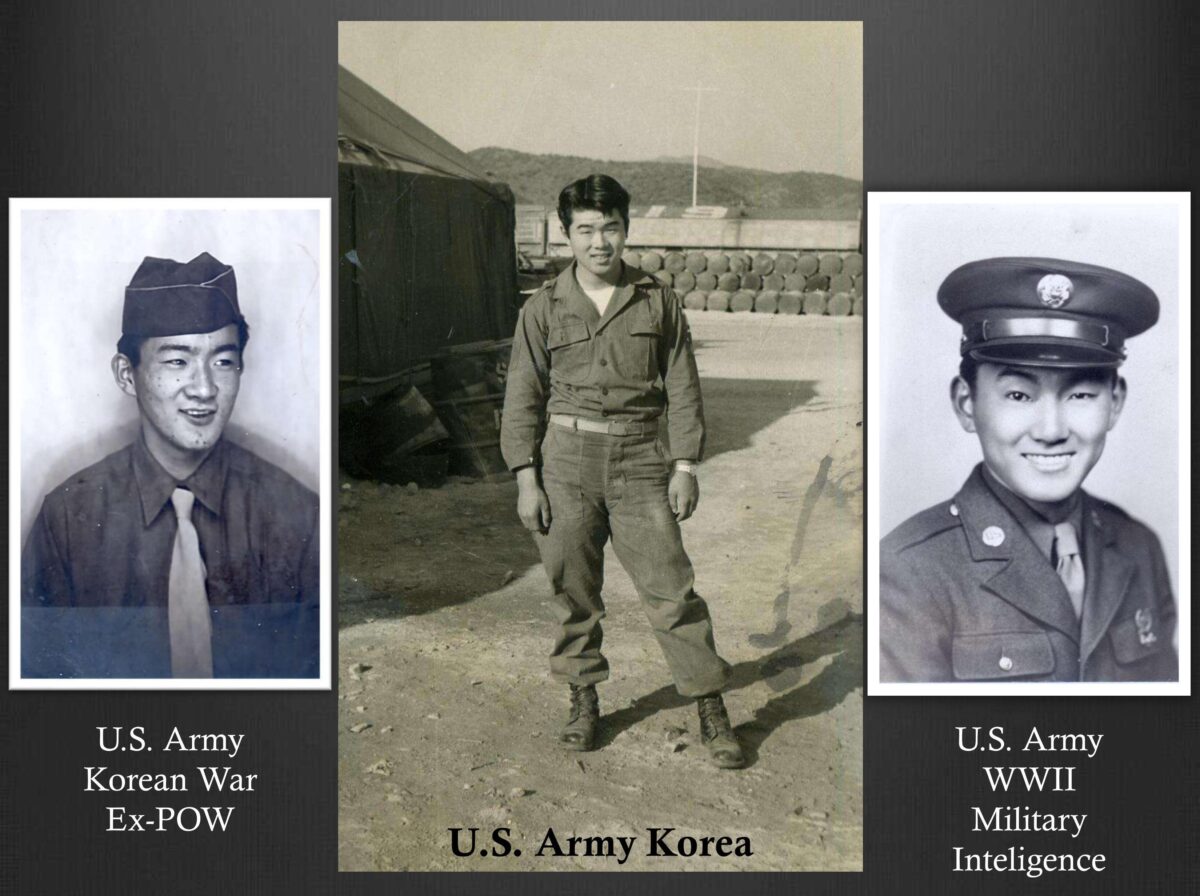

- Service photos of the Shimomura family. From left to right: Saburo Sam Shimomura, taken in 1951; Yukio Shimomura, taken in 1954; and Kenichi Shimomura, taken in 1946.

Image supplied, Yukio Shimomura

This Shimomura family photo was taken inside the Topaz War Relocation Center in 1944. From left to right: Taka Shimomura, Saburo Sam Shimomura, Kenichi Shimomura, Toshinaga Shimomura, Yukio Shimomura and Natsu Shimomura.

OGDEN — “Today is going to be a different kind of history class,” said Yukio Shimomura, a former internee of the Topaz War Relocation Center in central Utah.

Shimomura, an Ogden High School alumnus, shared his story with an auditorium of 11th graders at OHS on Thursday, of the day his life and the lives of all Japanese Americans changed when Pearl Harbor was attacked by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service.

As Shimomura began his presentation, he asked OHS students to imagine they were Japanese while he moved through clips of his childhood during WWII.

“This way they can feel it, smell it and experience it,” Shimomura said.

He said he does not know how many paragraphs are in the Utah textbooks about the U.S. internment camps, but he will try to fill in the holes.

Image supplied, Yukio Shimomura

Service photos of the Shimomura family. From left to right: Saburo Sam Shimomura, taken in 1951; Yukio Shimomura, taken in 1954; and Kenichi Shimomura, taken in 1946.

The United States declared war on Japan following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. “After Dec. 7, 1941, the whole world was in turmoil,” Shimomura said.

Everything was normal before the war, he said of his childhood in San Francisco riding his scooter up and down the streets. But that all changed once the U.S. joined the fighting.

With only the items they could carry, thousands of Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from their homes by May 1942 and placed in hastily constructed detention centers.

According to Shimomura, no one knew where they were going; they were just told they were going.

Many families temporarily stayed in horse stables at the Tanforan Race Track in San Bruno, California, before being relocated to the Topaz Internment Camp near Delta, where they lived for three years behind barbed wire with armed guards.

“You have to think the humanity of the situation,” Shimomura said.

Topaz was chaotic, Shimomura said, recalling the shooting death of an elderly man who had approached perimeter gates despite orders to turn around. Shimomura said they were incarcerated rather than relocated for their protection.

Those who defied Executive Order 9066 to report to an internment camp were arrested and convicted for military necessity, according to Shimomura.

There were 10 war relocation centers for Japanese Americans during World War II. Topaz, the only center located in Utah, reportedly had a peak population of 8,130 internees.

At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, there were approximately 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry living on the U.S. mainland, according to The National WWII Museum. Despite being ordered to confinement, more than 33,000 Japanese Americans served during the war, and approximately 800 of them were reportedly killed in action.

Shimomura said he remembers funerals being held inside Topaz for those who had died in combat.

In December 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ended the relocation program. Internees were free to return home, only many of them had no home to return to after being ordered out of their homes nearly three years earlier.

“You sold what you could for pennies on the dollar and left the rest,” Shimomura said.

Having been considered a national threat during the war, feelings toward the Japanese changed in the following years. According to Shimomura, many internees were fearful to leave the camps, not knowing what to expect from the outside world.

After leaving Topaz, Shimomura and his family relocated to Ogden, where his father took a position as a mail clerk at Anderson Jewelry.

Adjusting to life as one of the few Japanese American fifth graders was difficult, he said, adding that prejudicial treatment and derogatory words were common occurrences for the Shimomura family. It took a long time to get past the anger and fighting in defense of his honor and reach a point of understanding. “They were culturally deprived,” he said.

Junior high opened a new world for Shimomura upon meeting fellow football player Jim Hurst. The Hurst family accepted and loved Shimomura as though he were one of them.

With the respect and warmth he received from the Hursts, Shimomura graduated from Ogden High in 1953 as one of the most popular and highly respected members of his class, according to high school classmate Vance Pace.

“I believe he (Yukio) would be the first to admit that Jim saved his life,” Pace said.

Hurst and Shimomura were lifelong friends up until Hurst’s passing two years ago. An emotional Shimomura said the best years of his life were spent in high school as he stepped into the auditorium that had not changed in the last 69 years.