Utah’s earliest black pioneers almost forgotten, but not completely

Editor’s note: This story contains language some readers might find objectionable.

OGDEN — For much of the past 200 years, black people have been all but invisible in Weber County.

But history does offer a few hints about their earliest presence in what is known today as Utah.

The state’s Utah History to Go website — HistoryToGo.Utah.gov — offers a chapter titled ”Blacks in Utah History: An Unknown Legacy.” Written by Ronald G. Coleman, associate professor of history at the University of Utah, the article explains that the first black people came to the area almost a quarter-century before the arrival of the Mormon pioneers in 1847.

RELATED: What black history is — and what it is not

Among the first — and best-known — black explorers/fur-trappers in Weber County was James P. Beckwourth, a biracial man whose mother may have been a slave, according to Coleman’s piece. He was a trapper for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, as well as a guide, Indian fighter and hunter. He would have been in Utah sometime between 1824 and 1826 and spent time in what is now Ogden as well as the Cache Valley and Salt Lake City.

Coleman writes that there were other black explorers who were contemporaries of Beckwourth, including Jacob Dodson, who was about 18 years old when he volunteered for the John C. Fremont expeditions in Utah and the West. Dodson was paid $493 for services rendered between May 3, 1843, and Sept. 6, 1844, and Fremont reported that Dodson “performed his duty manfully throughout the voyage.”

RELATED: Black community members recall backlash in wake of horrific Hi-Fi murders

When the first Mormon pioneers reached the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, three black slaves — Green Flake, Oscar Crosby and Hark Lay — were among that original company. Their names are engraved on a tablet on the Brigham Young Monument at the intersection of Main and South Temple streets in Salt Lake City.

According to Coleman, folk tradition dictates that Flake was the one who drove the wagon that first brought Brigham Young into the valley.

“Black pioneers were both slave and free, Mormon and non-Mormon,” he wrote.

Historians know more about Flake than the other two, as he stayed in Utah longer. Crosby and Lay were part of a group of slaves taken to San Bernardino, California, in 1851, according to Coleman. He notes those two slaves were also freed at that time, since California law prohibited slavery.

Flake eventually moved to Idaho in 1885, but when he died, his body was returned to the Salt Lake Valley for burial next to his wife.

Among the black people coming to Utah with the Mormon pioneers, Coleman writes that at least three families were known to be free — the James family, the Abel family, and the Sion family.

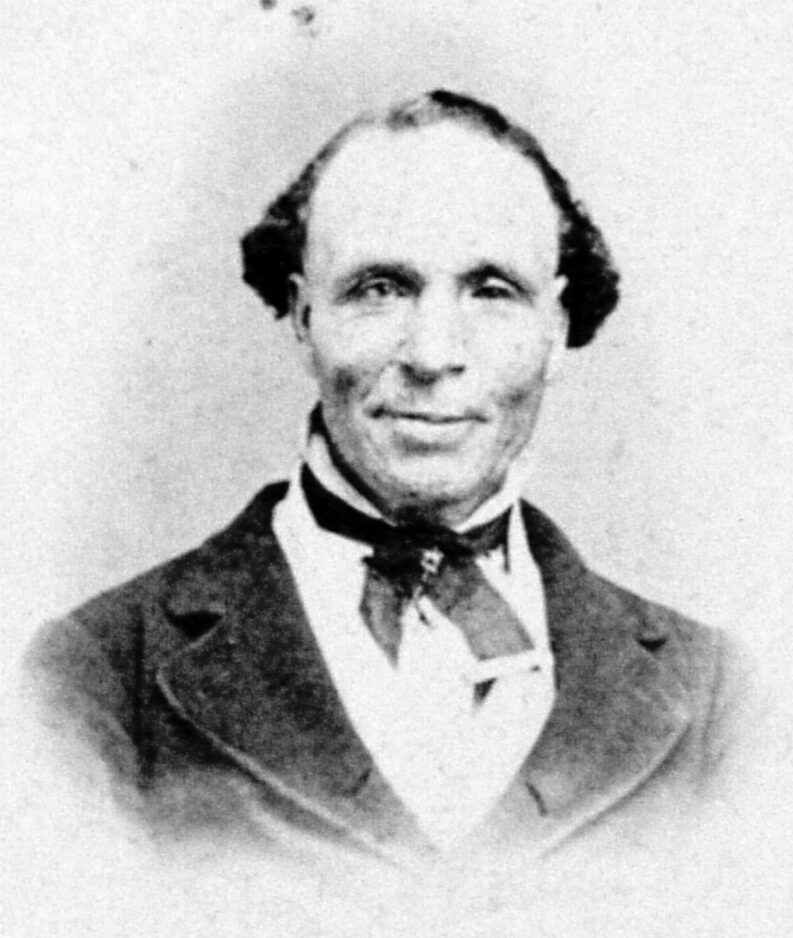

Elijah Abel was a biracial man who came to Utah with his family in 1847. The Abels lived in Ogden “for a short time,” according to Coleman.

Public Domain

Elijah Abel was ordained as an elder in the early days of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1836. He later moved to Utah, briefly lived in Ogden and helped build the Salt Lake City Temple.

Fredrick Sion, another biracial man, immigrated from England with his family in the 1860s. They eventually settled in Millville, in what is now Cache County, where he continued to work as a shoemaker.

It wasn’t until 1869, when the transcontinental railroad came to Utah, that the black population began to grow in Northern Utah, according to Richard Sadler, a historian and professor at Weber State University.

“We did not find a lot about blacks in Weber County before the railroad,” Sadler said.

Sarah Singh, curator of Special Collections at WSU, says the 1860 census shows no African-Americans living in Weber County. By the 1870 census, 21 black people were living in the county.

“It looks like most came because of the railroad,” she said.

Sadler offers one of the few references to black people in Weber County before the transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869.

“As the Union Pacific was being built west from Evanston (Wyoming), we do have record of a black man being killed,” Sadler said. “A paymaster wrote in his diary that a person was lynched here at Uintah.”

Coleman’s Utah History to Go article offers this straightforward take on the incident: “In 1869, a Black was shot and hanged at Uintah in Weber County. The reason given was ‘he is a damned Nigger.'”

“That’s a direct quote from the paymaster’s diary,” Sadler said.

With the coming of the railroad, black families began moving to Utah in search of relatively well-paying jobs.

“They begin to come and work here — particularly as porters and waiters,” Sadler said.

Eric A. Stene, a Colorado native who received his bachelor’s degree from Weber State in 1988, says the African-American community in Ogden saw much of its growth in the early 20th century.

“Prior to the early nineteen hundreds less than one hundred African Americans lived in Ogden,” Stene wrote in ”The African-American Community of Ogden, Utah: 1910-1950,” his thesis for his master’s degree from Utah State University. “The availability of jobs with the railroads brought many African Americans to Ogden in search of steady employment.”

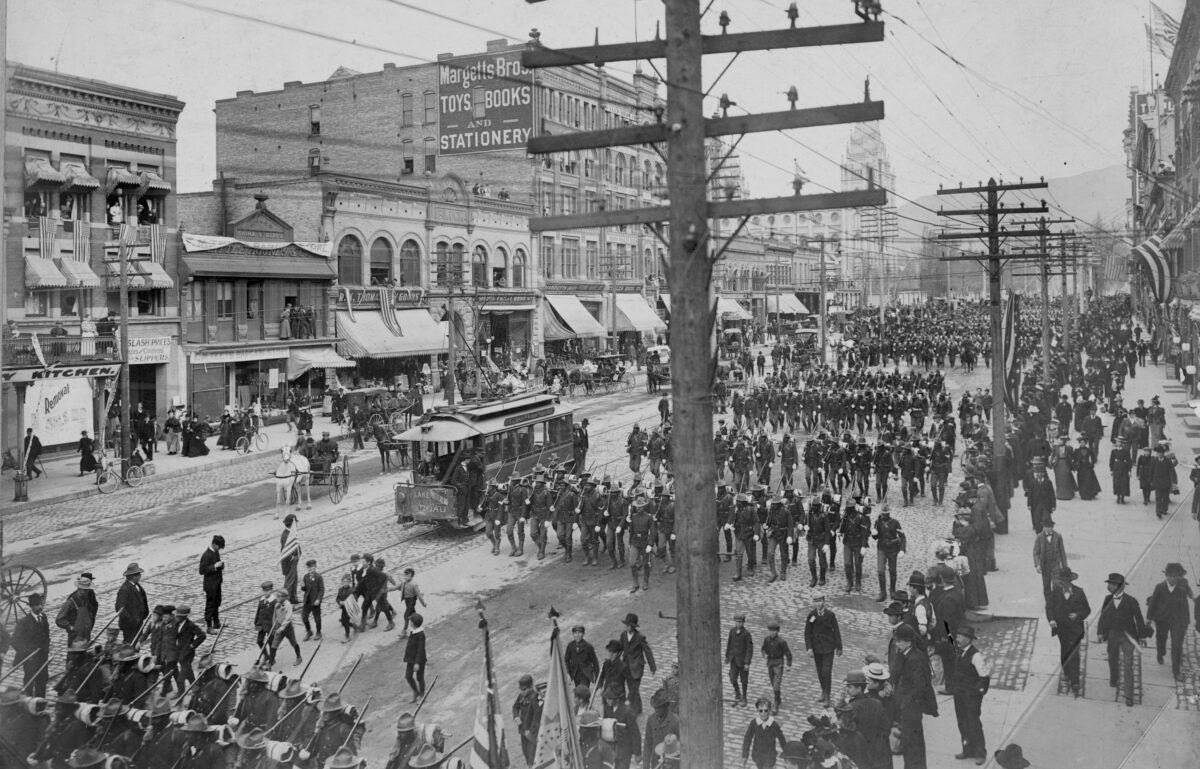

Story continues below photo.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

“24th Infantry Leaving Salt Lake City, Utah for Chattanooga, Tennessee, April 24th, 1898. African American soldiers marching down main street, while pedestrians look on.”

Stene says the black population in Ogden increased to between 200 and 300 between 1910 and 1940. An even more dramatic increase occurred in the 1940s with the growth of the war industry and added government jobs during World War II.

Between 1900 and 1950, the African-American population of Ogden went from 51 souls to 1,106, according to Stene.

“For many years Ogden had the second largest African-American population after Salt Lake City,” he wrote.

Sadler says Ogden mirrored other places of the time in its treatment of black people. And from a historical perspective, Sadler says the black experience hasn’t been a happy one.

“I think the issue is, in part, that we have not been kind to black people in this country,” Sadler said. “Slavery is an issue. And then there is an issue as well about the fact that, after slavery, we begin to deal with them very violently.”

Contact Mark Saal at 801-625-4272, or msaal@standard.net. Follow him on Twitter at @Saalman. Friend him on Facebook at Facebook.com/MarkSaal.